From 10 to 12 October, DCZ experts Eva Sternfeld and Michaela Boehme participated in the conference “Critical Agrarian Studies in the 21st Century” at China Agricultural University (CAU) in Beijing. The conference, which was jointly organized by the College of Humanities and Development Studies (CHUD) of CAU, the Journal of Peasant Studies (JPS), the Collective of Agrarian Scholar Activists from the South (CASAS), and the Transnational Institute (TNI), attracted more than 400 participants from 55 countries, including a delegation from the farmers’ activist movement La Via Campesina. In plenary sessions and parallel panels, the conference covered a broad range of issues from climate justice, migrant workers, gender perspectives, rural social movements, land rights, bio-politics of seeds, to land grabbing and many more. For the full program, please check here.

During the three-day conference it became clear that over the course of its 30 years, the CHUD has succeeded in being part of an excellent network of scientists and social movements in countries of the Global South. Particularly due to the commitment of the dean of CHUD, Prof. Ye Jingzhong, the excellently organized conference was able to take place after a long COVID-related absence. Given the wealth of contributions, only some presentations that explicitly dealt with topics in rural China can be mentioned here.

Theme 1: Agricultural modernization and rural migration

In his keynote speech, YE Jingzhong, who specializes in researching migration and particularly the “left behind population” in rural regions, addressed the challenges currently facing rural China due to changes in land use and demographic change. He reviewed the process of rural reforms over the past 40 years, from de-collectivization in the early 1980s to efforts to industrialize agriculture from the 1990s on to more recent attempts to involve small farmers in the process of modernization. In recent years, almost a third of small farmers have transferred their land rights to others. As of now, over 38 million hectares have been transferred.

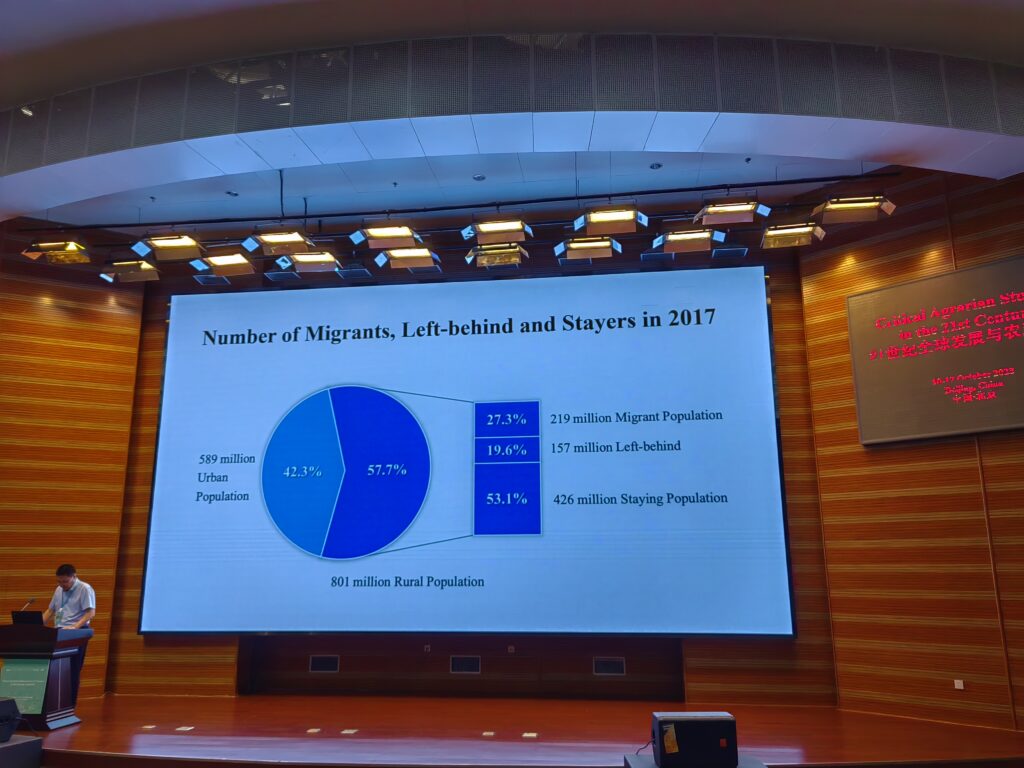

As Ye explained, there is a demographic problem behind this. China’s rural population is declining and aging. In 2017, almost 58% (around 800 million people) of China’s population were still registered as living in rural areas, but of these, over 200 million worked as migrants in the cities, while around 157 million people (19%) where counted as left behind and 426 million people (53%) as stayers. Agricultural production is therefore in the hands of the left-behind and stay-behind population. According to Ye, one could also speak of a feminization and grayization of rural regions.

In her presentation, ZHANG Ziwei (Harvard University) described the effects of migration and the costs for rural China. The migration of surplus labor is not only an economic question but also has an impact on the social and ecological reproduction of rural regions. This applies to the lack of care for children and the elderly, but also to the neglect of the repair of irrigation systems and the intensified use of pesticides and fertilizers due to a shortage of workers.

Theme 2: Structural change and the fate of small-scale farmers

Using the example of dairy farms in Shangdong Province, FENG Xiaojun (CHUD, CAU) showed how transformations take place in the agricultural sector. She described how, in the 1990s, smallholders switched from growing vegetables to dairy farming. In the early years, middlemen would buy their milk and deliver it to dairies. From 2015 onwards, a ruinous price war between dairies began, accompanied by protests of farmers, which gradually drove small farmers and later also the middlemen out of business. The dairy industry in China is nowadays dominated by large dairy farms.

Theme 3: Alternative models of rural organization

Several contributions dealt with alternative models of organizing small farmers in collectives and cooperatives. YAN Hairong (Tsinghua University) and DING Ling (Anhui Normal University) reported on Tibetan shepherds in Gacuo (Tibet) of whom many, when decollectivization was initiated in China in the early 1980s and the responsibility system was introduced, decided to retain the Maoist organizational model of the people’s commune. As in Maoist times, until today all proceeds flow into the commune’s budget and the commune members are paid according to a work point system. Pensions are also paid out to elderly commune members based on the points system. According to Yan and Ding, the Gacuo People’s Commune is very successful economically and the per capita income is currently 18,000 RMB per year, which is comparatively high for Tibetan herders.

Another contribution to this panel on collectivization was titled “Farmer’s organization for ecosocialism.” YU Huang (Minzu University of China) reported on the village of Xinxing in Jilin Province. The village has organized itself as a cooperative that jointly cultivates the village’s fields, owns agricultural machinery, and employs agricultural technicians who test different types of seeds in experimental plots. In this way, farmers can form a judgment as to which seeds are most suitable without blindly trusting the recommendations of seed companies.

Theme 4: International activities of Chinese agri-businesses

Other presentations dealt with the international activities of Chinese investors and agricultural companies. YANG Bin (Yunnan University) examined the investment strategies of Chinese agricultural companies in northern Laos. In his study, he showed that investors who invest in long-term agricultural projects (rubber and tea) also invest significantly more in local development projects (irrigation, temple construction, etc.) than those who invest in medium-term (bananas) or short-term projects such as vegetable cultivation. Accordingly, the attitude of the local population towards Chinese investors was ambivalent.

The presentation “The spread of Chinese hybrid seeds in Pakistan and Tajikistan” by Michael Spiess (Eberswalde University for Sustainable Development, Germany) discussed the effects of China’s going out strategy and “China’s new food silk road”. Using the example of imports of seeds for hybrid rice (Pakistan) and hybrid corn (Tajikistan), he showed that in recent years imports from China have increased significantly in both countries. They account for around a quarter of total seed imports. In the case of Pakistan, the company LongPing (named after the father of Chinese hybrid rice Yuan Longping) dominates the market. Chinese rice varieties are popular with Pakistani farmers because of their reliable high yields. However, Chinese rice varieties are mainly grown in Pakistan for export, while Pakistani basmati rice is preferred for domestic supply. Of the imports of corn seeds to Tajikistan, a growing share comes into the country via Chinese trading companies, although these are mainly seeds from multinational companies.

Further reading

Many of the contributions discussed at the conference will appear in future issues of the Journal of Peasant Studies.